Introduction

Note: This is the third article in a probably four part series, it will not make much sense without reading the other two:

- Creating A Google Home App where we get a very simple Google Home App up and running.

- Creating A Google Home App Part 2 - The Game where we turn that simple app into a game.

In the previous article we converted our very simple app into a version of Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock. In this article we will refactor our game, and then add scoring so the app will keep track of your wins and losses (initially it will be per session, and eventually we will have it keep track for all time).

As we stated in the previous article, our if else engine for determining game winners was very ugly. Let’s replace it with an array based engine, that will clean it up, reduce the amount of code, and remove a ton of hard coded strings. First we will create a pseudo enum with Object.freeze that has all of the 10 possible combinations of two people playing Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock (place this at the top of the rpsls.js file, after the options):

const GAME_CHOICES = Object.freeze({SCISSORS_VS_PAPER : 0, PAPER_VS_ROCK: 1, ROCK_VS_LIZARD:

2, LIZARD_VS_SPOCK: 3, SPOCK_VS_SCISSOR: 4, SCISSOR_VS_LIZARD: 5, LIZARD_VS_PAPER:

6, PAPER_VS_SPOCK: 7, SPOCK_VS_ROCK: 8, ROCK_VS_SCISSOR: 9});If you haven’t seen Object.freeze before it is a new feature added to JavaScript 5.1, that allows us to force immutable objects (in case you hadn’t noticed in the past, const isn’t really const as you can always add to or remove items from an array or object, with Object.freeze you will get an exception thrown if you try to mutate a frozen object). Javascript doesn’t really have enums, but this is pretty close. Next we are going to create an array of text outcomes based on our ‘enumeration’ (this also goes near the top of the rpsls.js file):

const OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS = {

[GAME_CHOICES.SCISSORS_VS_PAPER] : 'Scissors cuts Paper.',

[GAME_CHOICES.SCISSOR_VS_LIZARD]: 'Scissors decapitates Lizard.',

[GAME_CHOICES.PAPER_VS_ROCK] : 'Paper covers Rock.',

[GAME_CHOICES.PAPER_VS_SPOCK]: 'Paper disproves Spock.',

[GAME_CHOICES.LIZARD_VS_SPOCK] : 'Lizard poisons Spock',

[GAME_CHOICES.LIZARD_VS_PAPER]: 'Lizard eats Paper.',

[GAME_CHOICES.SPOCK_VS_SCISSOR] : 'Spock smashes Scissors.',

[GAME_CHOICES.SPOCK_VS_ROCK]: 'Spock vaporizes Rock.',

[GAME_CHOICES.ROCK_VS_LIZARD] :'Rock crushes Lizard',

[GAME_CHOICES.ROCK_VS_SCISSOR]: '(and as it always has), Rock crushes Scissors.'

};This way instead of duplicating our results like we previously were, we can use the same text for either computer beating the player, or losing to the player. Of course we could freeze this text too, as it won’t change, but for reasons only known to the author at the time he wrote the code, we have decided not to.

Next, instead of repeating strings throughout the code (and having the chance of misspelling scissors as scisors or sissors somewhere), we turn all of the user choices into another frozen Object Collection (place this at the top of the rpsls.js file as well):

const CHOICE_NAMES = Object.freeze({ROCK: 'rock', PAPER: 'paper', SCISSOR: 'scissors',

LIZARD: 'lizard', SPOCK: 'spock'});Next we create out choice matrix, this basically produces all the possible choices and contains their output. The users choice is the first part of the key, and the computer’s choice the second. Each element in the collection contains an outcome which is a string, and win – a boolean that indicates whether the player won or lost. We are placing this matrix again near the top of the rpsls.js file:

const CHOICE_MATRIX = {

[CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK + CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.ROCK_VS_SCISSOR], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK + CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.ROCK_VS_LIZARD], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK + CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.PAPER_VS_ROCK], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK + CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SPOCK_VS_ROCK], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER + CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.PAPER_VS_ROCK], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER + CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.PAPER_VS_SPOCK], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER + CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SCISSORS_VS_PAPER], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER + CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.LIZARD_VS_PAPER], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR + CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SCISSORS_VS_PAPER], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR + CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SCISSOR_VS_LIZARD], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR + CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.ROCK_VS_SCISSOR], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR + CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SPOCK_VS_SCISSOR], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD + CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.LIZARD_VS_SPOCK], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD + CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.LIZARD_VS_PAPER], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD + CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.ROCK_VS_LIZARD], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD + CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SCISSOR_VS_LIZARD], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK + CHOICE_NAMES.SCISSOR]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SPOCK_VS_SCISSOR], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK + CHOICE_NAMES.ROCK]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.SPOCK_VS_ROCK], win: true},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK + CHOICE_NAMES.PAPER]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.PAPER_VS_SPOCK], win: false},

[CHOICE_NAMES.SPOCK + CHOICE_NAMES.LIZARD]:

{outcome: OUTCOME_DESCRIPTIONS[GAME_CHOICES.LIZARD_VS_SPOCK], win: false},

};Now we can greatly simplify our returnResults code:

function returnResults(app, userChoice) {

const computerChoice = CHOICE_ARRAY[Math.floor(Math.random() * CHOICE_ARRAY.length)];

if (computerChoice === userChoice) {

app.ask(app.buildInputPrompt(true,

`<speak>

<p>

<s>I also picked ${userChoice}.</s>

<s>Try again, do you pick Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard or Spock</s>

</p>

</speak>`));

} else {

const result = CHOICE_MATRIX[userChoice + computerChoice];

if (!userChoice) {

console.error('Impossible choice: ' + userChoice);

app.ask('Something has gone wrong, you picked: ' + userChoice);

return;

}

let list = app.buildList('Start Game or Instructions');

list.addItems([

app.buildOptionItem(OPTION_AGAIN, ['Start', 'Yes']).setTitle('Again'),

app.buildOptionItem(OPTION_END, ['Stop', 'No']).setTitle('End')

]);

const message = '<s>' + result.outcome + '</s>' +

(result.win ? '<s>You Won!</s>' : '<s>You lost.</s>');

app.askWithList(app.buildInputPrompt(true,

`<speak><p>${message}<s>To play again, say again.</s>

<s>To quit say end.</s></p></speak>`), list);

}

}To see exactly what this looks like, you can look at the tag: PART_3_STEP_1.

Nothing here is particularly complicated, and it really has nothing to do with Google Actions so let’s skip along to our next change.

Next we are going to add per session scoring, as well as a bit of state so that we can provide better responses when we don’t get an answer we want. Our game state is going to be an enumeration, and there are basically 3 states: Initial, StartGame (when we are waiting for the user to choose Rock/Paper/Scissors/Lizard/Spock), and EndGame when we are waiting to see if they want to play again. Let’s create our version of an enumeration and place it at the top of the rpsls.js file:

const STATES = Object.freeze({INITIAL_STATE: 0, START_GAME: 1, END_GAME: 2});Next we need to keep the state somewhere, and this is done by adding the state to to every ask method (and askWIthList method). What is the state variable? It can be any JSON serializable object (i.e. you can’t shove something in that has circular structure, and an Object will lose any of its methods, but basically you can put any structure into the state object). If at any time during the interaction you don’t pass the state, it will revert to null so remember you have to set it everywhere, even if you don’t change it! The other thing to realize about state is that you are passing it back to the Google Servers and the Google Servers are passing it back to you with every request, so even though you can store fairly large objects in it, it may not be the most efficient way of doing things (you might want to store large objects in a local database instead).

The first place to add the state is in our mainIntentHandler. Since this is only executed when a user begins their conversation with our game, we can completely reset the state (including setting their wins and losses for this conversation to 0 – we will use these wins and losses later in the article).

function mainIntentHandler(app) {

console.log('MAIN intent triggered.');

const list = getStartList(app);

app.askWithList(app.buildInputPrompt(true,

`<speak><p><s>Welcome to Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock.</s>

<s>If you need instructions, say Instructions.</s>

<s>To play the game, say Start Game</s></p></speak>`,

['Say Instructions or Start Game']), list, {state: STATES.INITIAL_STATE, wins: 0, loss: 0});

}the only change in this function is the addition of the state at the end:

</speak>`, ['Say Instructions or Start Game']), list);becomes:

</speak>`, ['Say Instructions or Start Game']), list,

{state: STATES.INITIAL_STATE, wins: 0, loss: 0});Now we have to go and add state to all the rest of our Ask Commands. And to add state (unless we want it to revert every time), we have to get the state, which we do through the app method getDialogState.

So our readInstructions function (removing the ssml content) becomes:

function readInstructions(app) {

const list = getStartList(app);

const dialogState = app.getDialogState();

dialogState.state = STATES.INITIAL_STATE;

app.askWithList(app.buildInputPrompt(true, `..snip..`), list, dialogState);

}We set the state of the state variable (OK, perhaps a bit confusing, maybe we should have called it gameState), to be INITIAL when we reading the instructions. To start the game we do the same thing, except set the state to START_GAME:

function startGame(app) {

const dialogState = app.getDialogState();

dialogState.state = STATES.START_GAME;

app.ask(app.buildInputPrompt(true,

`<speak><p><s>Do you pick Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard or Spock</s></p></speak>`), dialogState);

}It is in returnResults that things really change:

function returnResults(app, userChoice) {

const computerChoice = CHOICE_ARRAY[Math.floor(Math.random() * CHOICE_ARRAY.length)];

const dialogState = app.getDialogState();

if (computerChoice === userChoice) {

dialogState.state = STATES.START_GAME;

app.ask(app.buildInputPrompt(true, `<speak><p><s>I also picked ${userChoice}.</s>

<s>Try again, do you pick Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard or Spock</s></p></speak>`),

dialogState);

} else {

const result = CHOICE_MATRIX[userChoice + computerChoice];

if (!userChoice) {

console.error('Impossible choice: ' + userChoice);

app.ask('Something has gone wrong, you picked: ' + userChoice);

return;

}

let list = app.buildList('Start Game or Instructions');

list.addItems([

app.buildOptionItem(OPTION_AGAIN, ['Start', 'Yes']).setTitle('Again'),

app.buildOptionItem(OPTION_END, ['Stop', 'No']).setTitle('End')

]);

dialogState.state = STATES.END_GAME;

dialogState.wins += result.win ? 1 : 0;

dialogState.loss += result.win ? 0 : 1;

const winLost = result.win ? 'You Won!' : 'You lost.';

const message = `<s>${result.outcome}</s><break time=".3s"/><s>${winLost}</s>

<break time=".5s"/><s >You have won

<say-as interpret-as="cardinal">${dialogState.wins}</say-as> games,

and lost <say-as interpret-as="cardinal">${dialogState.loss}</say-as> games.

</s><break time=".7s"/>`;

app.askWithList(app.buildInputPrompt(true,

`<speak><p>${message}<s>To play again, say again.<break time=".3s"/></s>

<s>To quit say end.</s></p></speak>`),

list, dialogState);

}

}The main change is that we update the state’s win and losses depending upon whether the play won or lost, and we tell the user their current win/loss state when telling them the outcome of the game.

The last change we make is to the textIntentHandler, because we now know the state of the game, we can handle invalid users much more intelligently, and give the user better feedback:

function textIntentHandler(app) {

console.log('TEXT intent triggered.');

const rawInput = app.getRawInput();

let res;

if (res = rawInput.match(/^\s*(rock|paper|scissors|lizard|spock)\s*$/i)) {

returnResults(app, res[1].toLowerCase());

} else {

const dialogState = app.getDialogState();

if (dialogState.state === STATES.START_GAME) {

app.ask(app.buildInputPrompt(true,

`<speak><p><s>${rawInput} is not a valid choice.</s>

<s>Do you pick Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard or Spock</s></p></speak>`),

dialogState);

} else if (dialogState.state === STATES.INITIAL_STATE ||

dialogState.state === STATES.END_GAME) {

const list = getStartList(app);

app.askWithList(app.buildInputPrompt(true,

`<speak><p><s>${rawInput} is not a valid choice.</s>

<s>If you need instructions, say Instructions.</s>

<s>To play the game, say Start Game</s></p></speak>`,

['Say Instructions or Start Game']), list, dialogState);

} else {

app.tell('Impossible choice, ending!');

}

}

} So, as you can see, we can tailor our results based upon our state. Also note that we don’t pass state to the app.tell method as that ends the conversation, and state is only kept around during the conversation. So everything to this point is available at the tag PART_3_STEP_2. Lets get our Simulator up and running again, so to do that we probably have to restart ngrok, get our new ngrok address:

ngrok http 5050

and place it in our rpsls.json:

"conversations": {

"main": {

"name": "main",

"url": "https://CHANGE-ME.ngrok.io",

"fulfillmentApiVersion": 2

}

} update gactions

gactions update --action_package PACKAGE_NAME --project rpsls-XXXXX

Start the app:

node index.js

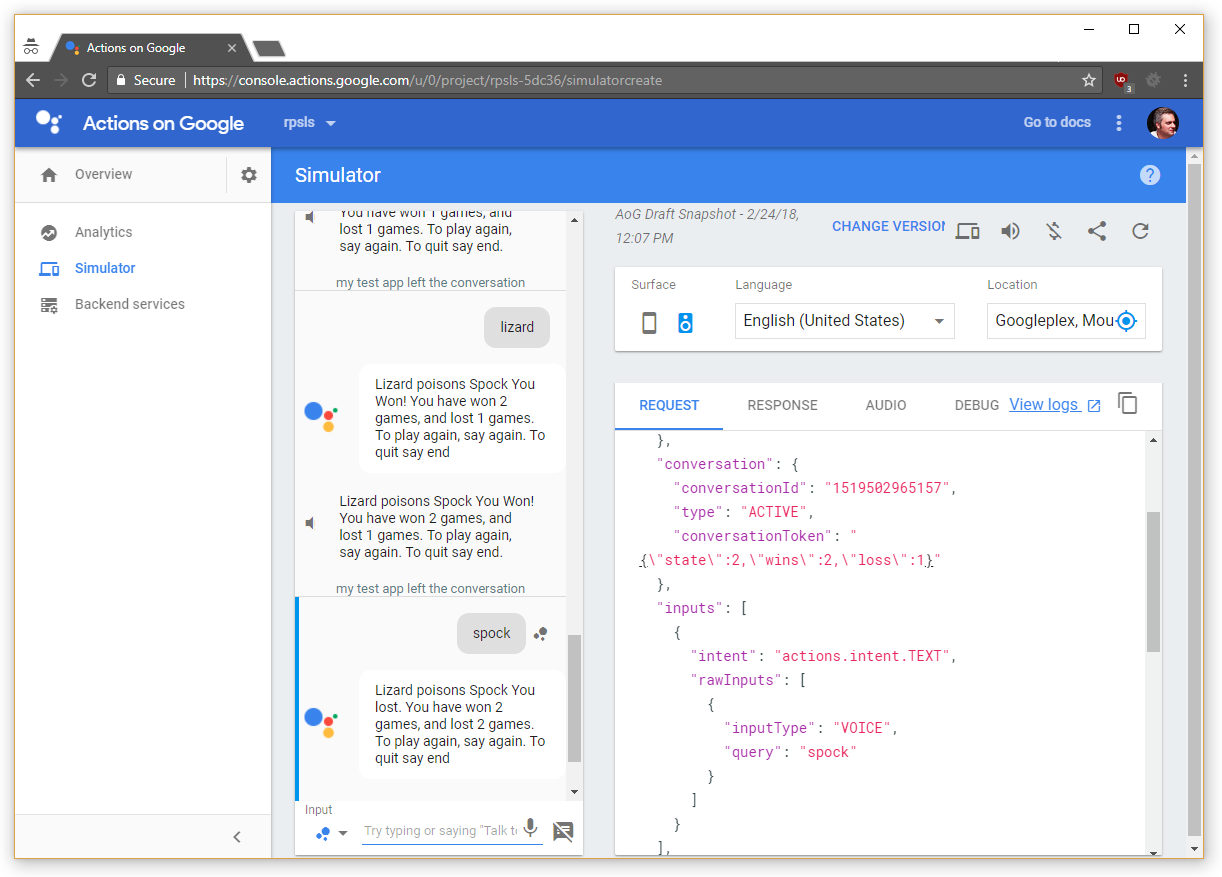

And then go to https://console.actions.google.com, go to the Overview of our project, and hit “Test Draft”. And now our app should be able to keep score:

You will notice that state is kept in variable called ‘conversationToken’, but we don’t have to worry about that as the Google Actions Node SDK takes care of all of that for us.

But what if we want to keep a running total of our wins and losses for all of our conversations with the Google Assistant?

Then we need to switch from state to user storage. The userStorage is available on the app object, and is maintained

from conversation to conversation. It has the same restrictions as the state does in what can be serialized on it,

and you should remember that anything you store in there will be kept (presumably) for ever (until you delete it)

and will always be sent to your service so remember to clean up items you don’t need. It is important to note (not that we would ever approach that size) that the serialized JSON for the userStorage is limited to 10K.

For our game, we can switch from using state to userStorage very easily. All we have to do is change a few lines of code, first in the middle of the returnResults function, were we set the dialog state, change the way scoring is tracked from:

dialogState.state = STATES.END_GAME;

dialogState.wins += result.win ? 1 : 0;

dialogState.loss += result.win ? 0 : 1;

const winLost = result.win ? 'You Won!' : 'You lost.';

const message = `<s>${result.outcome}</s><break time=".3s"/>

<s>${winLost}</s><break time=".5s"/>

<s >You have won <say-as interpret-as="cardinal">${dialogState.wins}</say-as> games,

and lost <say-as interpret-as="cardinal">${dialogState.loss}</say-as> games.</s>

<break time=".7s"/>`;to

dialogState.state = STATES.END_GAME;

app.userStorage.wins = (app.userStorage.wins || 0) + (result.win ? 1 : 0);

app.userStorage.losses = (app.userStorage.losses || 0) + (result.win ? 0 : 1);

const winLost = result.win ? 'You Won!' : 'You lost.';

const message = `<s>${result.outcome}</s><break time=".3s"/>

<s>${winLost}</s> <break time=".5s"/>

<s >You have won <say-as interpret-as="cardinal">${app.userStorage.wins}</say-as> games,

and lost <say-as interpret-as="cardinal">${app.userStorage.losses}</say-as> games.</s>

<break time=".7s"/>`;also we should remove the setting of the original win and loss state in the main intent handler, so that:

</speak>`, ['Say Instructions or Start Game']), list, {state: STATES.INITIAL_STATE,

wins: 0, loss: 0});becomes:

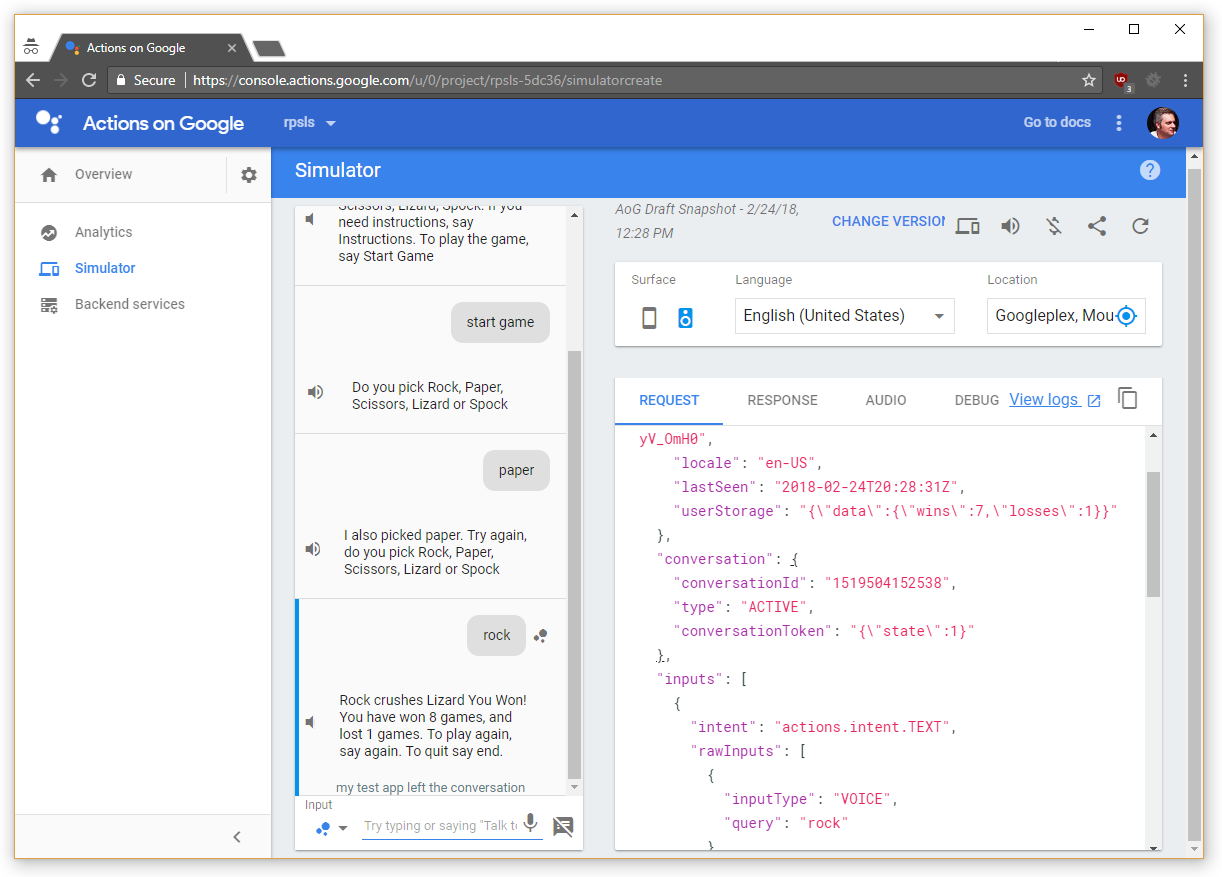

</speak>`, ['Say Instructions or Start Game']), list, {state: STATES.INITIAL_STATE});Now when we restart app, we see that our request object instead of storing wins and losses in the conversationToken, they are now stored in userStorage.

You can also see that I am apparently very good at Rock/Paper/Scissors/Lizard/Spock with a seven and one record! So what else could we possibly do to extend our Rock, Paper, Scissors, Lizard, Spock game? Well, we know how good I am at the game because I posted a chunk of JSON, but that is obviously no way to share it with our friends. To do that we need a site were we can have accounts were our scores are visible beyond the Google Assistant, and to the entire web. To do that we will have to

- Create a website with a login, a leader board, a sign up page, etc.

- Link that account to our Google Assistant Account through OAuth

- Profit!

But that will have to wait for the next (and probably final article) in this series on Google Home and the Google Assistant.